Covid-19 has had a devastating effect on the elderly across the world. Sometimes, as our body changes with age, symptoms can change as well. If we are not aware of this, early signs can be missed and delay intervention. Here is a translated interview with Professor Marcel Olde Rikkert, Professor of Geriatric Medicine at the Radboud University and hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, on this issue.

Covid-19 has had a devastating effect on the elderly across the world. Sometimes, as our body changes with age, symptoms can change as well. If we are not aware of this, early signs can be missed and delay intervention. Here is a translated interview with Professor Marcel Olde Rikkert, Professor of Geriatric Medicine at the Radboud University and hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, on this issue.

Originally published in NRC Handelsblad, 14 of May 2020

Author: Frederiek Weeda

Translation: Dr. Jan Weststrate

Editing: Kathryn Fernando

Marcel Olde Rikkert: “The elderly who have Covid-19 often show different symptoms than younger patients. Doctors were therefore put on the wrong track.”

“They have overlooked the elderly”, says Marcel Olde Rikkert. He calls it the “blind spot” in medicine. In the corona crisis – and especially in the initial phase during the great spread – they forgot how the older human body functions. “It’s as if we went back 20 years and knew nothing about geriatrics.” Olde Rikkert is a Professor of Geriatric Medicine at Radboud University Nijmegen and works in the hospital.

From December onwards, throughout the world the pandemic policy was determined by virologists, epidemiologists and infection doctors. Olde Rikkert: “All eyes were looking hopefully at them, the owners of the problem. And they looked at the virus, the exciting new virus from China: How does it spread and what does it do to organs. They did not look at the host who is most bothered by it: the elderly. While in China it immediately appeared that 85 percent of the deceased were very old.”

It was not a conscious policy, he says, rather a “mechanism that came into effect in response to an attack from an unknown angle.”

But there are now 9,053 elderly people in Dutch nursing homes infected with the virus. 1,696 of them died, professional association Verenso reported Wednesday (13-05-2020), 1,861 have recovered.

The older human body

The old body functions differently from the younger one, explains Olde Rikkert. That does not change at the same time for everyone. One is 85 but has a ‘biological age’ of 65 and is therefore relatively fit – “there are 100-year-olds recovering from Covid-19” – others are young, but have worn down organs: the lungs from smoking, the liver from drinking, diabetes from overweight. Or just because of bad luck.

But the big picture is: as the age increases, the blood vessels become narrower, the heart pumps less effectively, the blood flows less quickly and organs, and other parts such as brains and joints wear out. On average, eighty year olds have a body temperature of 35 to 36 degrees. The blood flow is restricted, so they are cold. If an eighty year old measures 37 degrees, she will have a fever if she is normally at 35 degrees. “But the corona guidelines of RIVM1 and WHO to this day speak of a corona suspicion from a body temperature of 38 degrees. This is not relevant for the elderly, ”says Olde Rikkert. “They often have Covid-19 infection without a body temperature of 38 degrees.”

Nineteen elderly

Geriatricians at the Elizabeth / Tweesteden Hospital in Tilburg already noticed this phenomenon in March. They decided to quickly collect examples together with Olde Rikkert and colleagues. In the Dutch (Journal of Medicine2 (NTVG) they described the first nineteen elderly who were admitted to hospital having tested positive for Covid-19 in Tilburg and Nijmegen. What turned out? “Of the nineteen very old patients, hardly any of them had two typical Covid-19 phenomena. At the most one. So they did not have the combination of symptoms that officially indicates Corona: 38 degrees fever, dry cough, shortness of breath. No, they sometimes had something completely different: they had delirium (acute confusion) or had fallen.”

The article, a “clinical lesson,” is the best-read piece online about corona at the NTVG, as more and more GPs saw sick old patients who didn’t understand what was wrong with them. And they did not qualify for a corona test at the GGDs without a high fever and cough, or two other “typical corona symptoms”.

Another difference with young people is that the immune system works less well in the elderly person. Olde Rikkert: “An attack by a flu virus or a virus like corona causes the older person’s immune system to become in the highest state of activity, but it does not fight effectively. There is a kind of immune storm, an overkill, and those can no longer be handled by the heart, lungs and brain (delirium).”

According to Olde Rikkert, policymakers looked at everyone in the same way in the corona crisis. “You really have to look differently at the elderly, they are constructed differently.”

Counting the dead

In the meantime, all nursing homes in the Netherlands have been closed by emergency ordinance since March 20. Visitors are no longer welcome, because nursing homes turned out to be real sources of infection. Family unwittingly brought the virus in and out. The elderly infected each other, and carers became infected. The strongest distribution occurred in wards for residents with dementia. Olde Rikkert: “If someone is demented, they don’t understand the isolation measures. It is difficult to separate a close-knit living group in a psychogeriatric ward.”

At the same time, corona deaths in nursing homes were not tracked. Because a large proportion of the sick elderly people had not been tested for the virus, they did not count in the RIVM1 statistics. They were not eligible for a test. Or two sick elderly people were tested in a ward and the other sick in that ward were also believed to have Covid-19. Verenso, the association of specialists in geriatric medicine, has started to do that from the end of March. “It is best to test because then you also know how to treat a patient and you can use protective equipment,” says Olde Rikkert.

In the back of the row

And perhaps most importantly, says Olde Rikkert: in March and April, the nursing homes were in the back of the line when the masks, aprons and glasses were distributed. The bulk went to hospitals. There was too little of everything. So little that the guidelines of the RIVM1 were adapted to it: “nursing home staff only work protected if the client is infected (or is suspected of it).”

It was not until April 20 that nursing home staff were given the right to be tested for corona immediately if in doubt. On April 23, a geriatric specialist was added to the experts from the Outbreak Management Team who informed the House of Representatives.

Vaccine

And even as scientists worldwide search for a corona vaccine, the older human body is forgotten, says Olde Rikkert. “All vaccine tests are done in people in their fifties! Those are the people who report for research. If you take a little more time and also test for those over eighty you may get a vaccine that will benefit the elderly. But it has to be done quickly, quickly.”

The goal should not be that vulnerable elderly survive as much as possible, he says. “Elderly medicine should add life to the days of old people and not add days to life. At COVID-19 you must therefore support the resilient, biologically young elderly in survival and also support the weaker elderly well by relieving the symptoms. If the latter succeeds, COVID-19 can also be “the old man’s friend”, as William Osler called pneumonia 100 years ago.”

He expects the “excess-mortality” of these months by the coronavirus to be followed by an “under-mortality”. “The people who would otherwise have died in the coming year have already gone.” And the elderly who survived Covid-19 will all be weakened. “People who have been infected are left with damage. People who are not infected but who are socially isolated also lose out. It has been proven to deteriorate your immune system.”

Not to mention loneliness in the precious time that the elderly have left. The elderly have been alone for a long time due to the intelligent lockdown. That is a paradox. Olde Rikkert ,”Because it is also the love for grandpas and grandmas, fathers and mothers, that is the cork that keeps the willingness of young people to engage in social distancing afloat.”

Notes

- RIVM is the abbreviation for National Institute for Public Health and Environment in the Netherlands

- 2. (https://www.ntvg.nl/artikelen/atypisch-beeld-van-covid-19-bij-oudere-patienten/volledig)

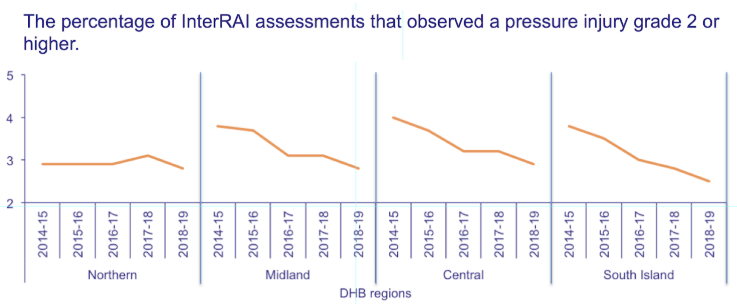

MOA is an online Quality Improvement Platform that is used by a large number of aged care facilities in Australia. The platform allows aged care providers (they call them partners) to self-assess and benchmarks their current performance against the standards, their past performance, and that of other providers using this platform. The self-assessment highlights risk and improvement opportunities that can be tracked and monitored in this digital platform for continuous improvement.

MOA is an online Quality Improvement Platform that is used by a large number of aged care facilities in Australia. The platform allows aged care providers (they call them partners) to self-assess and benchmarks their current performance against the standards, their past performance, and that of other providers using this platform. The self-assessment highlights risk and improvement opportunities that can be tracked and monitored in this digital platform for continuous improvement.